Are you A Worrier or Warrior?

They say stress is the silent killer. Whether it is relationships, finances, or exams, many aspects of our lives can be stressful. In certain circumstances, stress can be beneficial, by propelling us to accomplish difficult feats and allowing us to flee dangerous situations. However, often stress is an unwanted, unpleasant, and counterproductive feeling that has broad implications on one’s life and one’s health. Although many techniques have been suggested for stress reduction, some people find certain stressors unbearable and suffer adverse emotional and physical health outcomes as a result. Although stress management is within an individual’s control to some extent, specific genes also impact one’s ability to cope with stressful situations and the associated emotional and physical manifestations. In this brief column, we’ll describe the COMT genetic pathway and how it affects one’s tendency to deal with stress.

Our genes influence our response to stress

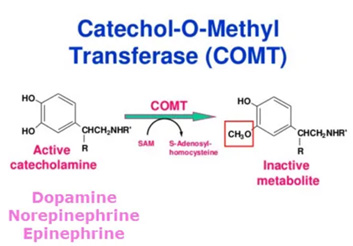

In part, stress resilience is underscored by the COMT gene. The COMT gene encodes the COMT enzyme, which influences the stress response through the metabolism of dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine in the pre-frontal cortex (PFC). Depending on the variant carried, one is said to be a “worrier” or a “warrior”.

- The “worrier” variant of this gene is associated with lower COMT activity which yields less metabolism of neurotransmitters and higher levels in the brain. “Worriers” tend to show less stress resilience and suffer from adverse feelings of anxiety and tension, changes in mood, and maladaptive behaviours.

- The “warrior” genotype is associated with higher COMT activity, increased metabolism of neurotransmitters and lower serum levels of dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine. “Warriors” benefit from this enhanced COMT activity and show superior stress resilience and improved physical and mental wellbeing, memory, and cognitive performance while under stress.

During stress

Worrier = slow COMT activity à increase in neurotransmitters in the PFC

Warrior = fast COMT activity à decrease in neurotransmitters in the PFC

So what can we do about it?

To overcome a poor stress coping genetic tendency, individuals can engage in preventative strategies that support relaxation though COMT-independent mechanisms.

- Consuming a diet rich in magnesium which is found in buckwheat flour, oat bran, halibut, wheat flour and spinach is one tactic.

- Avoid stimulants or other stressors will help to limit spikes in dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine. For example, caffeine and high-intensity exercise should be replaced by herbal tea and low-intensity alternatives.

- Engage in mindfulness activities 3-5 times throughout the day, this can be in the form of mindful breathing, walking or guided meditation.

- Health products such as magnesium threonate, L-theanine, phosphatidylserine and various medicinal herbs, such as licorice and passionflower are shown to positively reduce cortisol in those with chronic stress and improve perceived sense of stress.

By understanding your genetic blueprint, you can adjust your lifestyle and nutritional strategies to compensate for genetic predispositions. In this case, learn to incorporate stress management techniques to reduce basal cortisol levels and the tendency for elevations in neurotransmitters, along with helpful foods and health products to directly alter the effects of individual COMT genetic variations.

References:

- Jung, Y.-H., Kang, D.-H., Byun, M. S., Shim, G., Kwon, S. J., Jang, G.-E., Lee, U. S., An, S. C., Jang, J. H., & Kwon, J. S. (2011). Influence of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and catecholo-methyl transferase polymorphisms on effects of meditation on plasma catecholamines and stress. Stress, 15(1), 97–104. https://doi.org/10.3109/10253890.2011.592880

- Lonsdorf, T. B., Rück, C., Bergström, J., Andersson, G., Ohman, A., Lindefors, N., & Schalling, M. (2010). The COMTval158met polymorphism is associated with symptom relief during exposure-based cognitive-behavioral treatment in panic disorder. BMC psychiatry, 10, 99. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-10-99

- Same – S-adenosyl-methionine. Gateway Psychiatric. (2017, June 18). Retrieved March 14, 2022, from https://www.gatewaypsychiatric.com/same-s-adenosyl-methionine/

- Stein, D. J., Newman, T. K., Savitz, J., & Ramesar, R. (2006). Warriors versus Worriers: The role of COMT gene variants. CNS Spectrums, 11(10), 745–748. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1092852900014863