Precision Medicine – Gene-Based Dietary Guidelines for Successful Weight Loss

There are a plethora of dietary fads, expert opinions, and various strategies for weight loss, which often leads to feelings of overwhelm and difficulties knowing which diet is right for you. There are important questions to consider to help determine the diet that is most appropriate for an individual.

- Does your body respond better to a high or low-fat diet?

- Is it better to cut carbs or do you need more to fuel to support your activity level?

- Does meal timing affect the tendency for weight gain?

Most of us have or will approach these questions using a trial-and-error approach, which has merit, but takes time. However, with the motivation of new year’s resolutions most are looking for an efficient and effective strategy.

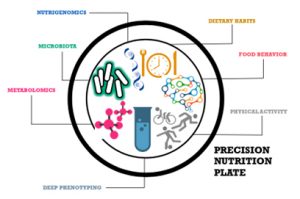

Precision nutrition utilizes genetic, biological, and behavioural data to curate a unique dietary approach for each individual. This method removes the time variable of the trial-and-error approach and maximizes benefits in weight loss, disease prevention and disease management, such as metabolic syndrome, high cholesterol, insulin resistance and diabetes.

(de Toro-Martín J, 2017)

A large part of precision nutrition is using the objective genetic data from large scale studies to determine the appropriate diet based on an individual’s DNA. This approach helps to determine a precise and effective diet that has a predictable outcome.

The following section is a breakdown of gene-based guidelines.

Macronutrient ratios

Total Fat

- Variations in the genes TCF7L2 and LIPC alter insulin and cholesterol levels in response to dietary fat and help to guide recommendations for total fat consumption.

- Studies show that those with the TT genotype of the TCF7L2 gene (rs12255372) have a larger decrease in BMI, total fat mass, and trunk fat mass (all P<0.05) after 6-months on a low-fat diet (< 20%) compared to CT and CC genotypes. In addition, those with the TT show better glycemic control with reductions in plasma glucose and insulin while consuming a low-fat diet.

- LIPC is a gene that produces a liver enzyme (hepatic lipase), which regulates lipoprotein metabolism and distribution of cholesterol throughout the body. Those with the T allele of the rs1800588 SNP have greater HDL cholesterol (HDL-C) concentrations when consuming less than 30% of energy from fat (P<0.001). On the other hand, when total fat intake is more than 30% of total caloric intake, HDL-C concentrations were lowest among those with the TT genotype, in comparison with CC and CT individuals.

Carbohydrates

- Variants in both the TCF7L2 (rs12255372) and CRY1 (rs2287161) influence insulin secretion, HOMA-IR (marker for insulin resistance) and the risk for type 2 diabetes (T2D). Numerous studies show that dietary modifications in carbohydrate quality and quantity modify the effects of these genes. Individuals with the TCF7L2 TT genotype have up to a 2-fold risk of developing T2D; however, the magnitude of the association is eliminated in those who consume a high fiber, low glycemic diet; while CRY1 CC genotypes who consume a low carbohydrate diet (< 41.65%) show an improvement in insulin sensitivity.

Protein

- Interestingly, the fat-mass and obesity (FTO) gene has a significant impact on response to protein intake and weight loss. Those who carry the at-risk A* allele who consume a hypocaloric (750kcal/d), high-protein diet exhibit fewer food cravings and reduction in appetite in comparison to people carrying the wild-type TT- genotype.

*Note: DNA Labs reports the forward strand of FTO, subsequently the risk allele is reported as T.

Eating Behaviour

Meal timing

- The circadian system is a physiological internal clock that works autonomously with the natural cycles and cues from our environment, such as variation in light during the day and night. This internal clock regulates various physiological functions, including metabolism. Research shows that variations in the PLIN1 gene alter weight loss in response to meal timing. Those with the at-risk variant who eat lunch after 3:00pm lose less weight (approximately 3kg) than those who eat lunch before 3:00pm.

Snacking tendencies and risk for weight gain

- Other food behaviors, such as the tendency for snacking are linked to genetics. Carriers of PER2 variants have more of an inclination to snack, especially during periods of stress or

- Studies also link variations in the FTO and MC4R genes with body weight. Variations in the MC4R gene influence appetite and satiety leading to higher tendency for snacking, while carriers of the at-risk variant in the FTO gene have a 1.7-fold increased risk of obesity due to higher postprandial leptin and tendency to consume excess calories.

- The melanocortin-4 receptor (MC4R) gene influences appetite and satiety in the hypothalamus and multiple aspects of body weight regulation, including overall body weight, weight loss response, and/or weight loss maintenance. For at-risk variations with a reduction in MC4R activity and higher tendency for snacking, a greater emphasis on increasing energy expenditure through physical activity is helpful to compensate.

While there are other genes that influence dietary response, DNA Labs has chosen those with the largest effect for FeedMyGenes gene-based diets. FeedMyGenes curates precise dietary recommendations using an individual’s genetic report with predictable effects weight loss and disease prevention and management.

References:

- Dashti HS, Smith CE, Lee Y-C, Parnell LD, Lai C-Q, Arnett DK, et al. CRY1 circadian gene variant interacts with carbohydrate intake for insulin resistance in two independent populations: Mediterranean and North American. Chronobiol Int. 2014 Jun;31(5):660–7.

- de Toro-Martín J, Arsenault BJ, Després J-P, Vohl M-C. Precision Nutrition: A Review of Personalized Nutritional Approaches for the Prevention and Management of Metabolic Syndrome. Nutrients. 2017;9(8).

- Fenwick, Peri H., et al. “Lifestyle Genomics and the Metabolic Syndrome: A Review of Genetic Variants That Influence Response to Diet and Exercise Interventions.” Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, vol. 0, no. 0, Feb. 2018, pp. 1–12. Taylor and Francis+NEJM,

- Gardner CD, Trepanowski JF, Del Gobbo LC, Hauser ME, Rigdon J, Ioannidis JPA, et al. Effect of Low-Fat vs Low-Carbohydrate Diet on 12-Month Weight Loss in Overweight Adults and the Association With Genotype Pattern or Insulin Secretion. JAMA. 2018 Feb 20;319(7):667–79.

- Mattei, Josiemer, et al. “TCF7L2 Genetic Variants Modulate the Effect of Dietary Fat Intake on Changes in Body Composition during a Weight-Loss Intervention123.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, vol. 96, no. 5, Nov. 2012, pp. 1129–36. PubMed Central

- Ordovas, Jose M., et al. “Dietary Fat Intake Determines the Effect of a Common Polymorphism in the Hepatic Lipase Gene Promoter on High-Density Lipoprotein Metabolism Evidence of a Strong Dose Effect in This Gene-Nutrient Interaction in the Framingham Study.” Circulation, vol. 106, no. 18, Oct. 2002, pp. 2315–21. circ.ahajournals.org,

- Phillips CM. Nutrigenetics and metabolic disease: current status and implications for personalised nutrition. Nutrients. 2013 Jan 10;5(1):32–57.

- Weedon MN. The importance of TCF7L2. Diabetic Medicine. 2007;24(10):1062–6.

- Xu M, Ng SS, Bray GA, Ryan DH, Sacks FM, Ning G, et al. Dietary Fat Intake Modifies the Effect of a Common Variant in the LIPC Gene on Changes in Serum Lipid Concentrations during a Long-Term Weight-Loss Intervention Trial. The Journal of Nutrition. 2015 Jun 1;145(6):1289–94. 1.