Exploring the Link Between Infant and Maternal Secretor Status on Infant Susceptibility to Viral Gastroenteritis and Celiac Disease

Blog Post by Indrani Das and Aaron Goldman, PhD

We are thrilled to announce the publication of a review article that explores the combined effect that secretor status (more on this below) has on a child’s susceptibility to gastroenteritis and Celiac Disease. Understanding how certain genetic variants impact risk can potentially be used as part of a preventative strategy to minimize the likelihood of developing disease. These genes include HLA and FUT2, and are covered as part of our LoveMyHealth® Nutrition and Lifestyle DNA Test panel.

Celiac Disease (CeD) is a disorder where the body mistakenly attacks its own small intestine when someone eats gluten, a protein found in wheat, barley, rye, and grains. This attack damages the gut and interferes with the body’s ability to absorb nutrients properly. The disease affects about 1.4% of people globally, and the number of cases has been growing over the years.

Various factors can raise a person’s chance of getting CeD, including genetics, environmental triggers, and certain gut infections. The most well-studied genetic variants, or “alleles”, associated with CeD include the HLA-DQ2 and HLA-DQ8 alleles, and testing for six SNPs within this gene region has become the ‘gold standard’ genetic test for Celiac Disease risk (found under “Gluten”, within the “Sensitivities” section of the LoveMyHealth® report). These risk alleles are almost always found in people with CeD: 95% of patients with CeD carry the HLA-DQ2 genotype and 5% carry the HLA-DQ8 genotype. However, not everyone that carries these alleles go on to develop CeD – while 30-40% of people carry these alleles, only about 3% of them end up getting CeD. This risk increases when you have a close family member with CeD. Factors like eating gluten, getting gut infections, changes in the abundance of different bacterial species in the gut, and breastfeeding can set off the disease in people with these genes. Gastroenteritis, a common intestinal infection, has been found to increase the risk of CeD, especially if it occurs in early childhood.

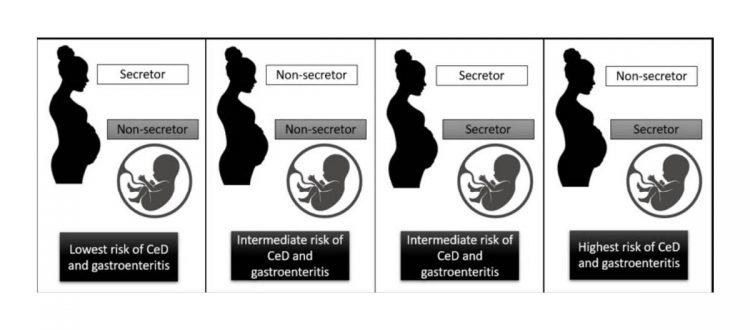

A person’s ‘secretor status’, determined by the FUT2 gene (found under “Probiotics”, within the “Specific Nutrient Needs” section of the LoveMyHealth® report), also plays a significant role in this complex relationship between gastroenteritis and CeD. Secretor status affects what type of blood group markers a person has in their body fluids. Secretor status can also affect our chances of getting stomach bugs like rotavirus and norovirus. Individuals with the secretor trait can produce certain molecules that these viruses use to invade our cells. Research shows that if you have the secretor trait, you are more likely to get sick from certain of these viruses because you have more of these ‘docking stations’ for the viruses. When viral infections lead to gastroenteritis, this may make the gut more permeable, allowing gluten to enter the bloodstream more easily, which could raise the chances of developing CeD. Overall, individuals, including infants, with the secretor trait are at higher risk of viral gastroenteritis caused by viruses like rotavirus and norovirus. On the other hand, those with the non-secretor trait have some protection against severe rotavirus infections. To complicate things further, the secretor status of the mother can have a lasting impact as well. Breast milk from mothers with the secretor trait contains antibodies that provide protection from infections, including gastroenteritis. It also contains Human Milk Oligosaccharides (HMOs), which are essential for the establishment of a healthy gut microbiome in infants. A balanced gut microbiome is crucial for the infant’s immune development.

The composition of the gut microbiota also plays a role in CeD susceptibility, whereby certain alterations in the gut microbiome have been associated with an increased risk of CeD. Our genes also influence the kinds of bacteria living in our gut, and these bacteria can affect our health. For instance, those with the secretor phenotype tend to have more diversity and a greater abundance of certain beneficial bacteria, like bifidobacteria, compared to those with the non-secretor phenotype. Infants breastfed by mothers with the non-secretor phenotype may experience a delay in the establishment of beneficial gut bacteria, and can lead to an increased risk of CeD.

In conclusion, understanding an infant’s genes, along with their mom’s genes, can allow for early screening and preventative measures to reduce the onset and severity of diseases like CeD. Since our DNA doesn’t change over the course of our lifetimes, our LoveMyHealth® Nutrition and Lifestyle DNA Test is a one-time test that can be carried out on infants and the report can be a valuable resource throughout their entire life. Taking into account both the infant’s and the mother’s genetics could potentially lead to new strategies to prevent stomach flu and CeD, such as tweaking the level of certain immune chemicals in breast milk, giving babies specific probiotics, or vaccinating babies against stomach flu viruses. While more research is needed to validate these approaches, we’re excited about the potential impact that genetic testing can have on disease prevention.

Dr. Aaron Goldman, PhD

Chief Science Officer